Updated:

Keep

More than 500 years have passed since that field near the Valladolid town of Villalar became the scene of a crucial battle in the future of the History of Spain. In that wide plain, the troops loyal to King Carlos V sentenced the comunero movement in 1521, which, although it barely survived for a while longer, might not overcome that resounding defeat and the execution of its leaders Juan Padilla, Juan Bravo and Francisco Maldonado. That April 23 was recorded in the memory of what is now the autonomous community of Castilla y León, which chose the anniversary for its party. But that date also left indelible marks on the land where hundreds of men lost their lives, scars that neither time nor plowshares have erased.

In a recent archaeological study carried out by the company Patrimonio Inteligente SL, a dozen pieces associated with the war have been recovered, such as several spherical lead projectiles used by the arquebusiers, 1.5 centimeters in diameter and between 14 and 16 grams of weight, among them one deformed by the impact, as well as some coins of the Catholic Monarchs that were in legal tender at that time. “These are evidences clearly attributable to the battle,” archaeologist Ángel Palomino tells ABC, satisfied with having managed to contribute “archaeological material” to what was known regarding the confrontation.

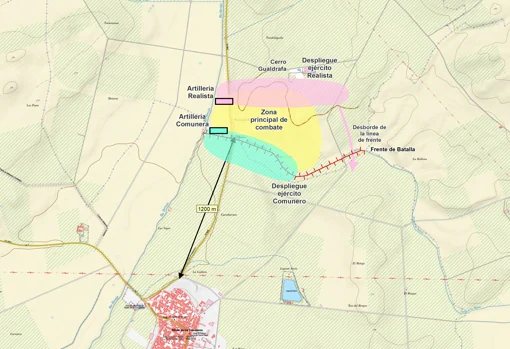

The survey of the area with metal detectors and georeferencing systems has allowed us to better understand how the battle took place. According to the account of the events, which was collected by chroniclers of the time such as Pedro Mártir de Anglería, Juan Maldonado, Pedro Mejía, official chronicler of Emperor Carlos V, or Alonso de Santacruz, the community troops left the castle of Torrelobatón at dawn on the 23rd of April bound for Toro. Although their forces, between 6,000 and 7,000 men, were similar in number to those of the royalists, the commoner ranks were made up mostly of infantrymen supported by some artillery that they had gathered and some 500 horsemen. Carlos Barroso Martín, professor of History at the Miguel de Cervantes European University in Valladolid, explains that it was a poorly trained and poorly armed army, while the royalist troops gathered by the nobles in neighboring Peñaflor de Hornija had more experience in the art of the war and were far superior in cavalry, numbering over 2,000 mounted soldiers. Aware of their shortcomings, the community members thought that in Toro, a day’s journey away, they might protect themselves better.

As soon as the royalist observers realized that the community forces were abandoning Torrelobatón at dawn, they notified the Constable of Castile, Íñigo Fernández de Velasco, and the staff in Peñaflor, who decided to send the cavalry, with some artillery campaign, in pursuit, ahead of the infantry. That day it rained persistently, a factor that played once morest the community members. The rain made it difficult for the tanks and artillery pieces to advance on those muddy terrains and also wet the gunpowder and the fuses of the arquebusiers.

Archaeological investigations have shown that the community members formed a front line in the Los Molinos stream, entrenching themselves in a ravine to try to contain the advance of the royalists who arrived from the north, from the town of Marzales. “That’s where the positioning of the front takes place, where the community artillery makes some unloadings, in very bad conditions due to the rain, and from there, from Puente el Fierro to Marzales is where Padilla makes several incursions and where the main skirmishes take place. Palomino explains. The projectiles found in the surroundings of the Los Molinos stream and in the direction in which it seems that the community arquebusiers fired indicate this.

How long they would hold out before the royalist cavalry broke that line and a rout among the community members is unknown. From then on, more than a battle it was “a hunt”, according to experts. With the rain wetting the gunpowder, without the possibility of moving the cars through the mud, and facing a much more numerous and professional cavalry, Padilla’s men might do little. “Between the stream and Villalar is where the massacre of the community members takes place,” says Palomino.

It has been thought that perhaps some managed to gain a foothold in Villalar, firing an artillery piece, but the archaeologist clarifies that according to the surveys carried out “it does not seem that this happened”. “Some surely reached the town, but in disarray.” The royalist cavalry was far superior and in an area of open country the comunero soldiers were helpless before those galloping horses that were thrown at them. The chronicles refer that many community members changed sides, taking off the red crosses they wore in rebellion.

“Although climatologically it rained for both sides, the superiority of the royalist side in cavalry that day, at that time, in that place, perfect for some charges, had the upper hand,” says the historian of the Miguel de Cervantes University . With no place to defend themselves, with their artillery damaged by the rain, with their ranks plunged into chaos, the comuneros found themselves hopelessly defeated. Some chroniclers speak of some 500 casualties on the commoner side. His captains were arrested and executed the next day.

This first attempt to approach the archaeological reality of the battle of Villalar through magnetic detection has yielded “interesting” results, in the opinion of the Smart Heritage team, which encourage further research in a broader and more intensive way. Until now, everything that was known regarding the battle came from documentary sources and not very precise regarding the event, explains Palomino. “There was a ‘damnatio memoriae’ and an important silence during the reign of Carlos V and Felipe II. It is above all from the 19th century onwards when the memory of the comuneros began to be recovered with the liberal revolts and when research began “.

Juan Martín Díez, the Stubborn, prepared a file in 1821 “very clear regarding it,” continues the archaeologist. Although 300 years had passed, the memory of daggers, swords or helmets found in the area was preserved. Archaeologists have still now found a tool used by the arquebusiers to make projectiles and a crossbow point, among the hundred pieces from different periods that they have come to locate.

Some of them come from the military camp that he set up in the Villalar el Empecinado field during the commemoration of the third centenary of the battle. “Some store pikes and some regimental buttons have come out that have to do with that military parade in 1821,” says Palomino.

Clemente González García, an archaeologist specializing in the archaeological study of battlefields, has collaborated in the survey commissioned by the Junta de Castilla y León last year, on the occasion of the V Centenary of the commemoration of the battle. It was a first sampling, in which, for example, the location of the pit where the fallen in battle ended up was not investigated. There are references to the burial of the remains in the surroundings of one of the Villalar churches. “We are considering addressing it in a broader research project,” Palomino advances. The recent finds encourage archaeologists.